Author: Manaswita Sarkar, SPH Media | Member IAB SEA+India Data, Measurement & Impact Regional Council

It has been five years since GDPR signalled a paradigm shift in the way digital marketers target audiences and measure performance.

The need for a first-party data strategy is now widely understood, as shown by a Deloitte-Google study across 70+ APAC app-developers and publishers in 2022. Yet a recent Adobe study shows that 79% of APAC brands are still increasing investment in cookie-based activations.

This is because a brand’s first-party strategy often required a long gestation period for data collection from customers and leads, especially in industries like Consumer Packaged Goods where traditionally there was no need to have recorded user data. Even then, a brand may not have access to all the types of targeting data required for meaningful segmentation and marketing.

So, for many brands the conversation has shifted from first-party data strategy to data partnerships.

Marketers today are hard pressed to find a consolidated guide on how to navigate the business, technological and legal aspects of data-sharing in the context of marketing, making implementation a long and complex process. Organisations including SPH Media who are frequently part of data-sharing conversations, have come up with their own internal frameworks.

Regulatory and industry bodies such as the Infocomm Media Development Authority (IMDA), The Association of Banks in Singapore (ABS) and Reserve Bank of India (RBI) have defined frameworks for data sharing for their respective industries and geographies. However, understandably, their focus has remained on the technical, commercial and legal aspects.

In this industry discussion summary I will outline the considerations specific to using data-partnerships for marketing use-cases.

The four key areas of consideration are:

-

Use-case definition.

-

Sourcing of data.

-

Technological considerations including inter-operatibility, infrastructure, and governance.

-

Legal considerations on applicable policies, laws and contractual scope.

Use-case Definition:

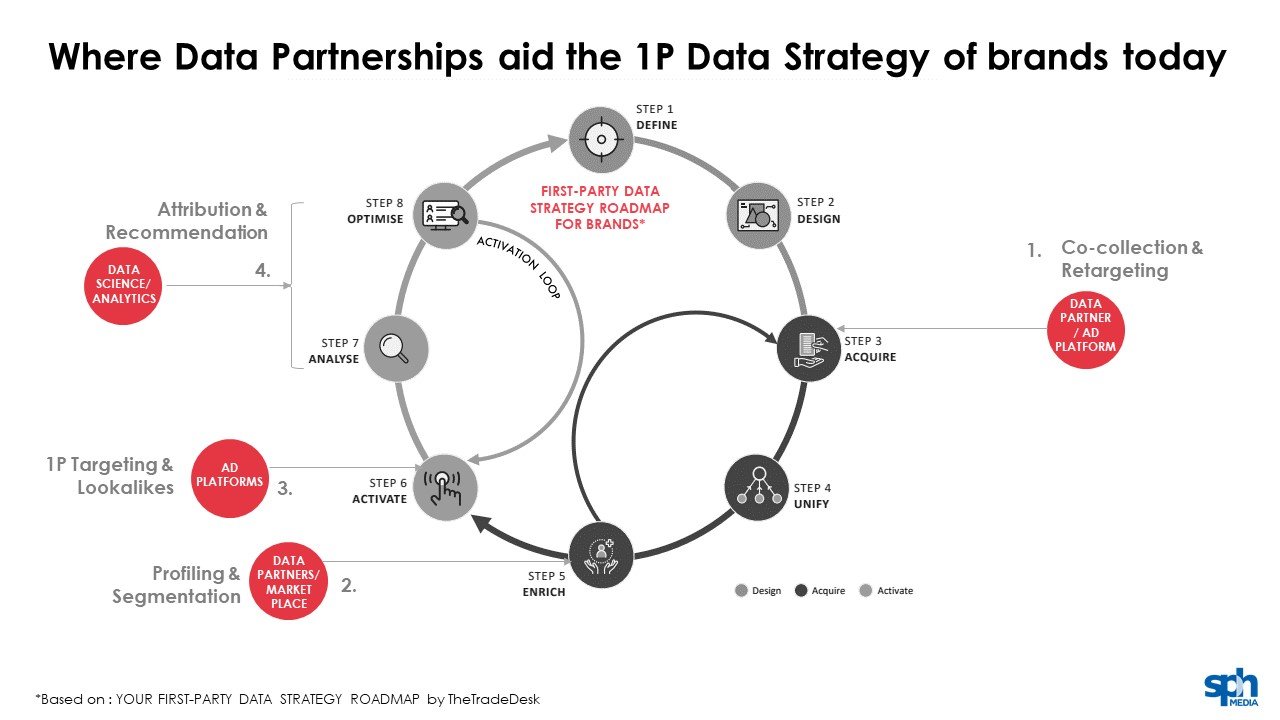

A good starting point is to take a look at one’s first-party roadmap (used below is The Trade Desk’s template) and see which of the steps require external supplementation of data.

Traditionally data partnerships have revolved around:

- Joint data collection : Examples include partnerships between banks and organisations running credit card rewards programs.

- First party targeting : This involves a brand uploading its first-party data into an ad platform for inclusion or exclusion targeting based on user-matching.

As partnerships evolve, three new categories of use cases are emerging:

1. Profile enrichment : The third-party deprecation schedule has ramped up advertiser interest in profiling of their own users based on reading behavior on various publisher websites and even taking this user-level data back into their system for below-the-line marketing efforts. Other examples of profile-enrichment include sister companies within a conglomerate pooling their respective resources on customer data.

2. Analytics : Either aggregated or at a user level. Some interesting analytics use cases in Singapore have been between Singapore telcos and tourism operators for analysing mobility data to plan their event marketing.

3. Cross-platform attribution : This involves matching campaign impressions from multiple partners against retailer conversions to calculate the ROI of each value chain.

Sourcing of data:

Although traditionally data-partnerships have referred to direct exchanges negotiated between two brands with alignment needed from the highest levels of the organisations. Increasingly, however, with marketers leading data partnership discussions, there are new out-of-the box solutions becoming available.

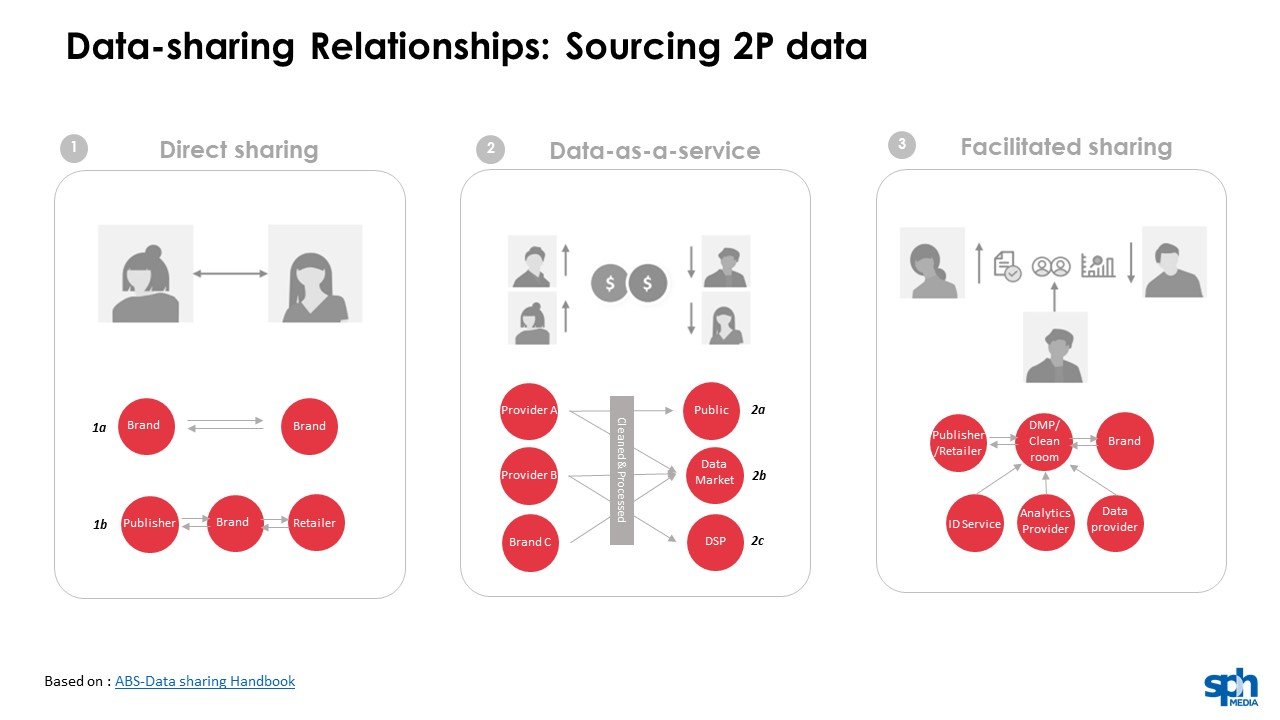

The IMDA and ABS recognise three major ways data is exchanged or bought. The choice depends on the level of investment and involvement an organisation wants in building the necessary infrastructure on their end or to pursue a data partnership, as well as the ready availability of the data they want.

- Direct sharing Bilateral or multi-lateral partnership between data provider(s) and data consumer or an exchange between providers. Any two or more companies that are part of a marketing or distribution value chain can benefit from exchanging data.

- Data as a Service (DaaS) Where a data provider or data-rich company prepares its data in a format usable by multiple parties with the least tech investment in terms of tech set up. Marketers can simply buy this from a second-party data marketplace.

- Facilitated data sharing When a platform which has existing data relationships with multiple parties, they create a common ecosystem with an identity resolution system. Examples include DMPs, CDPs and data cleanrooms.

partner selection:

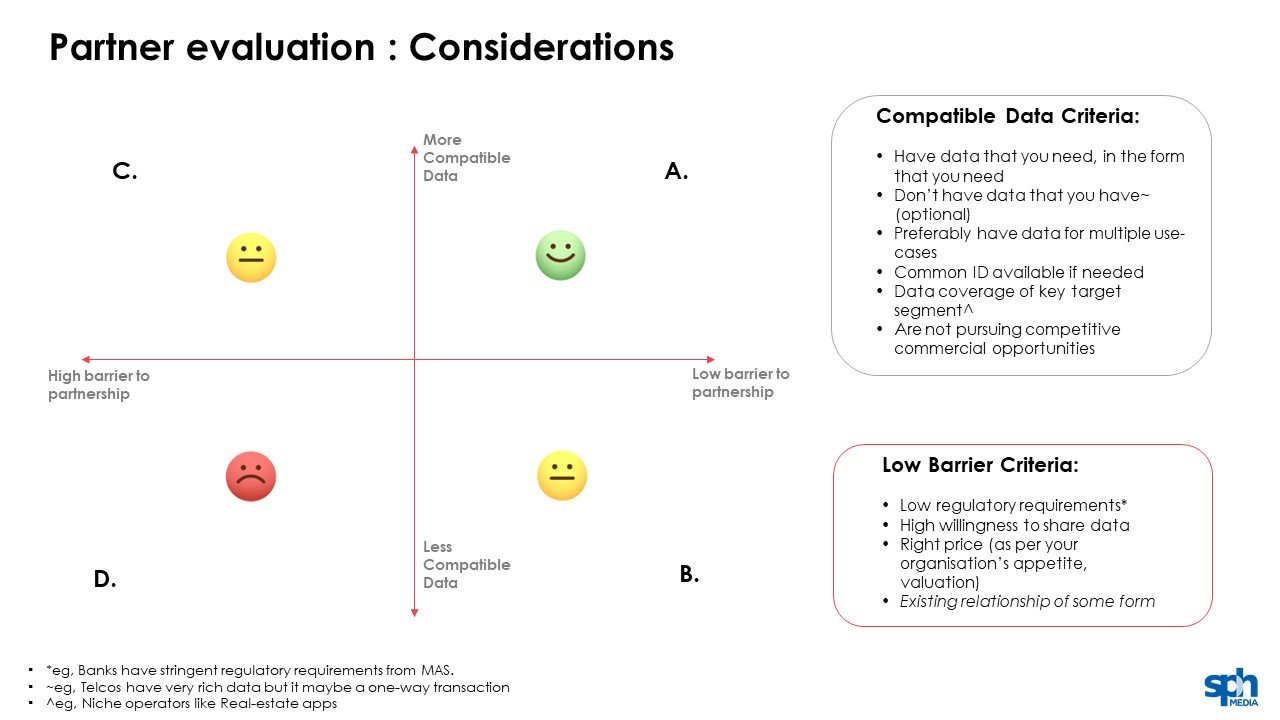

While DaaS and facilitated sharing allow one to pick and choose data across multi partners, direct-sharing typically requires careful evaluation on data compatibility as well as of entry-barriers to the partnership.

- Compatibility of data – Considerations include identifying partners who are likely to have information on one’s target audience, at scale, against an inter-operatable ID (more on this later) and is not pursuing competitive commercial opportunities.

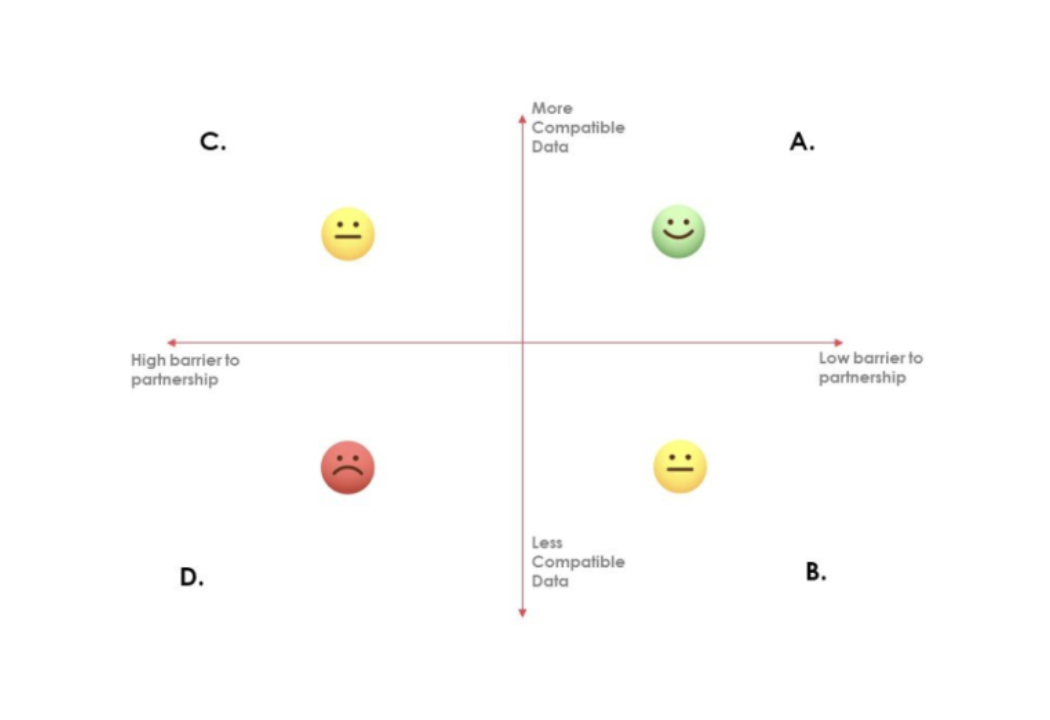

- Entry-barrier – Industry legislation, pricing, willingness to share are the considerations. While quadrant A is obviously the most desirable, whether to choose quadrant B or C depends on the organisations’ appetites to transform attributes where required, or to compensate in monetary terms.

TECHNOLOGICAL READINESS

Common ID : Privacy-regulations aside, this can still prove to be a deal-breaker, especially for user-level attributes. An example maybe a commercial real-estate company trying to plan mall tenants by overlaying granular demographic data by postcodes from one partner, with interest profiles from a partner who stores this information against phone numbers.

While incorporating data partnership into the holistic data strategy, it may be worthwhile to plan for which IDs to map one’s user data against.

- PII user ID – Selecting this might aid internal user-data unification and maximise common currency with data rich organisations. However, considerations include:

- Collection and value-exchange.

- Consent that is fit for purpose.

- Anonymisation and hashing needs (eg, SHA256 hashing) to be privacy-compliant.

- Universal ID – Can help an organisation to plug into an existing ecosystem of demand-side or supply-side partners.

- Selecting a probabilistic or deterministic ID solution based on the scale and specificity needed (eg, probabilistic for targeting or recommendation use cases, vs deterministic for attribution use cases).

- Which ID has the highest adoption in the industries with which one needs to share data.

The identity landscape keeps evolving. More information is available in IAB SEA + India’s series on Identity Resolution in a Cookieless World.

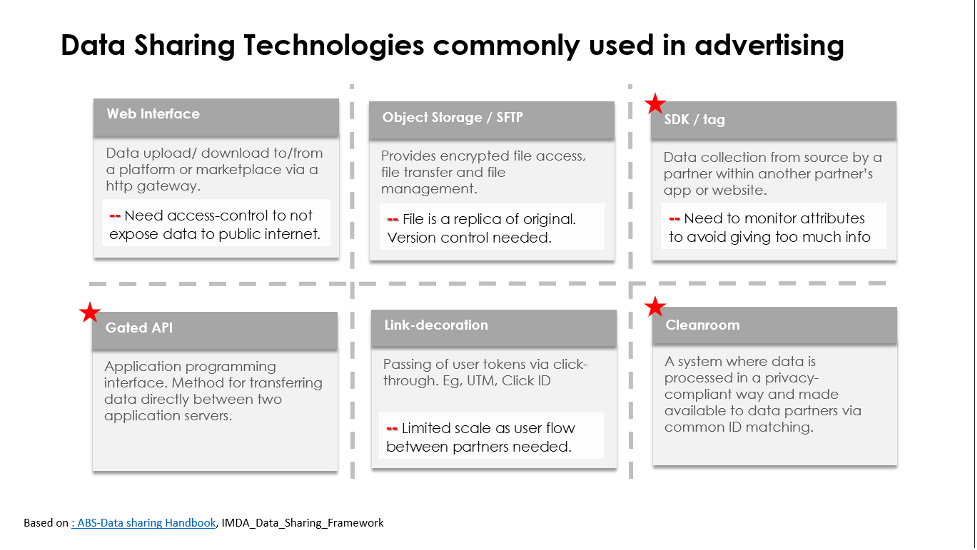

The choice of data sharing and processing technology is important both from a strategic capability standpoint as well as from a security standpoint.

Strategic considerations include the organisation’s future direction on how deeply data partnerships are ingrained into the business model, whether in terms of reliance on second-party data or as a potential revenue source. This would determine the level of control it would want on the processing, retention and downstream analytics or activation.

Governance considerations should include:

- Upstream and downstream use cases: Whether downstream systems such as analytics tool are enabled with the same access and encryption capabilities as required by the sensitivity of data. Wherever possible anonymization, tokenization and masking should be used as required.

- Storage and Handling: Considerations include availability. Eg, for use-cases like dynamic landing page where audience data needs to be processed in real-time, one may need tags that retrieve and store segment information via edge technology and first-party cookies.

- Retention policies: Duration and security should be pre-agreed based on each partner’s information security policies.

Data cleanroom technology is considered the current front-runner for an optimal balance between a level of operational control and privacy. Some cleanrooms already offer existing integrations with analytics, machine learning, and downstream ad-network integration.

Legal and Regulatory Considerations

The final consideration is a watertight partnership agreement that is compliant with industry and company regulations, as well as those of the countries an organisation and its partners operate in.

2. Industry Laws:

- Company data governance policy on data sharing and movement out of company.

- Industry regulations on customer data.

- Eg, RBI paper on account aggregation for banks in India, MAS privacy policy guidelines for banks in Singapore.

2. Geographic Laws pertaining to:

- Region of the organisation’s operation.

- Regions where an organisation’s data moves or is used.

- Regions from where data is collected.

- Eg, Cookie consent in GDPR vs PDPA in Thailand or Singapore.

3. Contractual Scope:

- Is purpose clearly stated?

- Are data-points shared proportionate to purpose?

- Are protection requirements aligned with data sensitivity?

- Eg, Is sharing customer email necessary for profile exchange on common customers?

Of course, one must also define what success looks like for the data partnership. While this is outside this discussion’s scope, this can manifest as potential to generate new revenue through the partnership, either in the form of targeting efficiencies, new product ideas, or monetisation of the combined data assets.